The JPMorgan Equity Premium Income ETF (JEPI) 2023 prospectus says it “…captures a majority of the returns associated with the S&P 500 Index while exposing investors to lower volatility than the S&P 500 Index and also providing incremental income.”

The prospectus for its sibling, the JPMorgan Nasdaq Equity Premium Income ETF (JEPQ), says the same thing (using Nasdaq as the benchmark).

In fact, of the several dozen covered call ETFs out there, most say the same thing, they 1) generate current income by 2) replicating some benchmark and writing a call option on it, and 3) deliver volatility mitigation along the way.

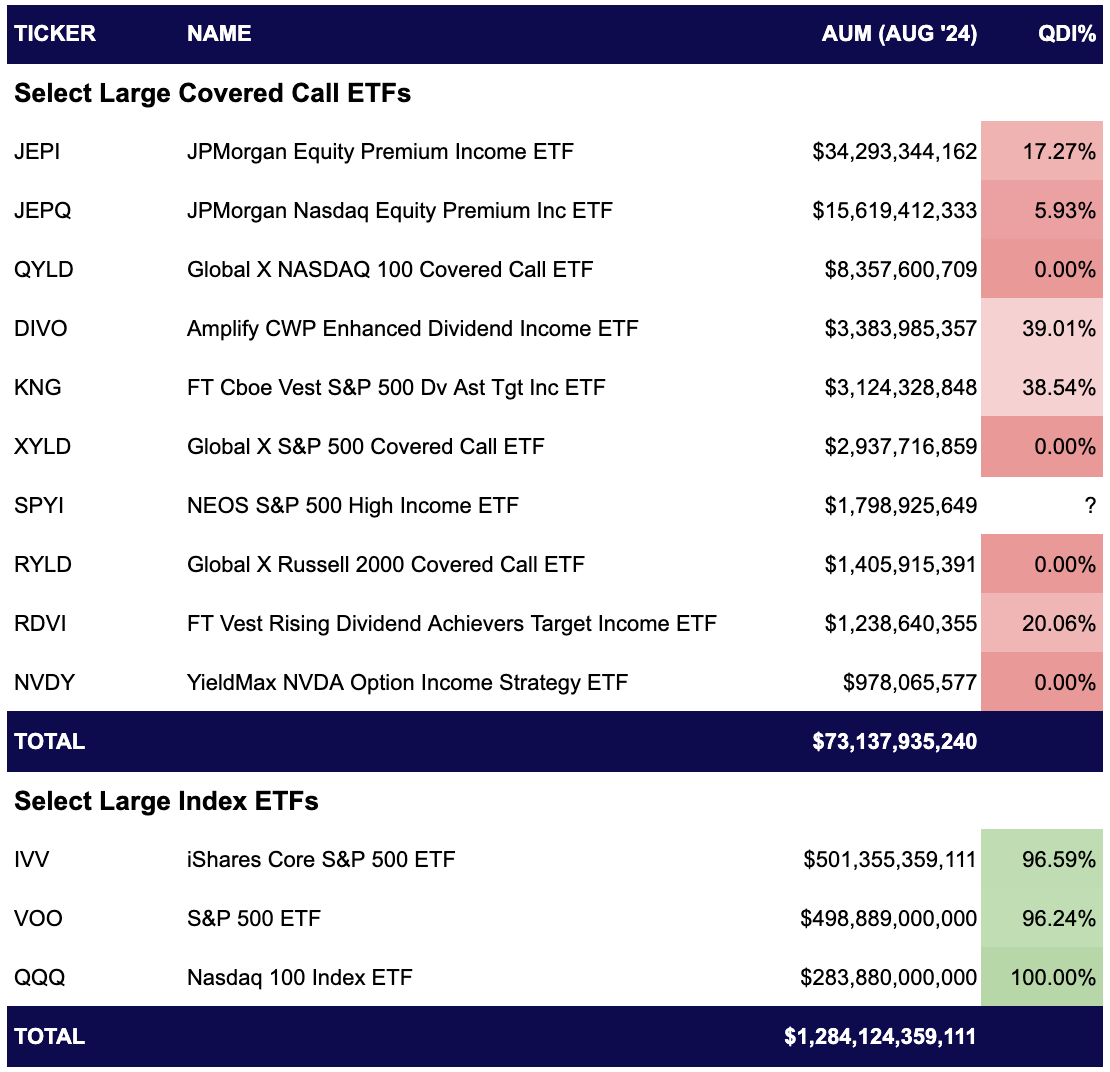

This pitch is effective. The Morningstar category, called “Derivative Income,” has amassed around $80 billion AUM.

Covered call ETFs generate income by writing a call option on some underlying. The call's strike caps the growth of the underlying. In general, investors have traded upside potential for current income.

Is this a good thing?

Plenty of folks have investigated the viability of the covered call fund on a pre-tax basis, so I’ll keep it brief.

Since stocks tend to go up, forgoing upside for current income seems like the equivalent of a child failing the marshmallow experiment. In other words, if you take the cash now (one marshmallow), you give up something in the future (another marshmallow).

“The covered call is a poor strategy for generating income,” Hossein Kazemi, a professor serving as editor of the Journal of Alternative Investments, wrote in the editor’s letter to the Spring 2024 issue after he compared XYLD (Global X S&P 500 Covered Call ETF) with a plain vanilla S&P 500 ETF.

Volatility mitigation is also part of the equation.

“[T]he option premium may provide a small cushion to the downside risk of the asset,” S&P researchers wrote in a 2017 paper on covered calls.

But the smart money isn’t buying it: “Institutions looking to generate income would stay away from a covered call strategy because of the 100% downside risk and negative convexity,” Yang Tang, CEO of Arch Indices and sponsor of the VWI multi-asset minimal volatility income ETF, told me. “If institutional investors who have deep expertise in options and derivatives are not interested, there's little reason for advisors or retail investors to favor this.”

Moreover, ”[I]n a quest for income, not only is a covered call investor likely accepting lower total gross returns, but they are also likely paying higher taxes along the way for the privilege,” wrote Roni Israelov and David Nze Ndong in their 2024 paper “A Devil's Bargain: When Generating Income Undermines Investment Returns.”

That’s a whirlwind tour of the arguments against covered call ETFs. I’ve skimmed over the nuanced and interesting points about equity premium and short volatility premium and how they fit into a portfolio because this article is about tax. So, let’s get to it.

Tax

Tax makes the case for covered call ETFs worse in two ways:

Quantity: Tons of taxable events

Quality: Lots of short-term capital gains and possibly ordinary income

Quantity

Every time a covered call ETF writes an option, it produces cash and a tax liability. The liability is payable when the option closes, but payable nonetheless. Investors, thus, give up upside potential and the option to defer tax. As you'll see, there is a tax deferral trick many covered call ETFs use involving tax-loss harvesting, but the investor is always on their heels fending off new taxable events.

Assignment is another source of taxable events. When a call option buyer exercises their option, the writer of the option must sell the underlying security at the strike price. The Options Clearing Corporation randomly assigns this obligation to firms. A covered call writer usually realizes a capital gain since they typically write options a little out-of-the-money.

These things don’t happen in plain-vanilla index ETFs. The cash stays in the portfolio and keeps growing. Covered call ETFs have more tax drag than index ETFs by the sheer quantity of taxable events.

It gets worse.

Quality

If the original sin is the taxable event itself, the second sin is how poorly each event is taxed. A covered call ETF has essentially three sources of tax liability:

Premium income

Realized capital gains

Dividends

Premium Income

A covered call ETF might hold the underlying and write all the options directly or use an equity-linked note as JEPI (and its NASDAQ sibling do).

An equity-linked note is a bond that pays interest. Interest is taxable as ordinary income. That's as bad as it gets. You'll see why in a minute.

In the plain-vanilla-covered call case, the ETF holds the underlying and writes the options and any premium received is taxed as short-term capital gains. This is bad, but not as bad as ordinary income.

Many covered call ETF portfolio managers understand tax and they get that passing short-term capital gains to shareholders is not a good look.

To defray the tax liability associated with option premiums, many ETF sponsors, whether they advertise it or not, harvest losses on the underlying and try their darndest to net those losses against the premiums received.

Even if they pull it off, many covered call ETF investors still expect income. So, the ETF distributes a “return of capital,” which is not taxable. Since a return of capital is like giving the investor their money back, the portfolio basis declines. This has the net impact of deferring taxation on premium income into the future. That’s good.

An aside about return of capital…

Return of capital comes in two forms, which I’ll call “funded” and “unfunded.”

Funded return of capital is supported by portfolio growth and income, while unfunded return of capital is not.

For example, if a $100 portfolio (with $100 basis) generates $5 in premium income, and harvests $5 in tax losses, and NAV grows to $110, then its RIC distribution requirement (to avoid taxation at the fund level) is $0 (90% * $5 in premium offset by $5 in losses). A $2 dividend may fortunately be classified as return of capital. The portfolio basis falls to $93 ($100 - $5 harvested - $2 ROC), which effectively kicks the taxation of the option premium into the future.

On the other hand, if a $100 portfolio (with $100 basis) generates $5 in premium income, and harvests $5, but NAV declines to $95, then its RIC distribution requirement is also $0. A $2 dividend may be classified as return of capital, and the portfolio basis also falls to $93 as in the previous example. The key difference is that the fund’s NAV has fallen, and it cannot sustain this level of distribution.

How do you know the difference between funded (good) return of capital and unfunded (bad) return of capital? The folks at Parametric (see their article below) write that “…if the NAV has increased, the fund earned more than it distributed. If the NAV has gone down, the fund distributed more than it earned.” You want the former kind.

Investors can learn more about the nature of return of capital by looking at Form 19a-1, which explains the character of distributions. Here’s an example, with the helpful reminder that “A return of capital does not necessarily reflect [the fund’s] investment performance and should not be confused with “yield” or “income”.

Investors may also see Form 8937 Report of Organizational Actions Affecting Basis of Securities, here’s an example, which describes the basis adjustments following a return of capital.

Tax-loss harvesting is a clever but partial solution to the original sin of having many taxable events.

It's important to remember that tax-loss harvesting potential decays over time. With each harvest, the basis of that position declines until it's practically impossible to continue harvesting.

This isn't a problem if investors keep contributing cash to the ETF since it can keep buying and establishing a higher basis. But who knows if these ETFs will stay popular.

Circling back to JEPI’s use of the equity-linked note, since its character is ordinary, tax-loss harvesting (which produces capital losses) doesn't work. Investors cannot net ordinary income and capital gains. So, the portfolio keeps any harvested losses captive for use against future gains, but the premium income, taxable at the highest marginal rates, passes directly to investors.

Finally, it's important to remember that writing calls produces income no matter the market environment. In the most obnoxious scenario, a portfolio that has lost money must still pay the tax bill for option premiums received.

Realized capital gains

Assignment

One of the ETF wrapper's "dirty little secrets" is its ability to indefinitely defer capital gains tax by coordinating in-kind redemptions. That's a mouthful and a topic that's received hundreds of pages of lawyer/professor analysis, industry research, and press coverage. I won't rehash it here.

The thing you need to know is that ETFs are preposterously tax-efficient due to in-kind redemption. But in-kind redemption isn’t much use if an ETF is forced to sell because it was assigned. Selling usually produces a capital gain, and depending on the fund's structure, the gains may be short-term and taxed at the highest marginal rates.

Tax straddles

You don’t need to understand the details of the tax straddle rules. You just need to know that they generally force investors to defer losses into the future. Deferring gains is good. Deferring losses is bad.

There are two ways to deal with tax straddles:

Avoid them entirely

Use the mixed straddle election to lessen the blow

Some funds, like Parametric’s PAPI, deliberately construct their portfolio to side-step the straddle rules by keeping “…the overlap between its stock holdings and the stock holdings of the Underlying ETF or constituents of the Underlying Index to less than 70%…” (2024 prospectus). The tradeoff is that there’s a difference between the written call and the underlying portfolio.

Other funds, like Global X, charge head-first into the straddle rules but attempt to lessen the blow by making the mixed straddle election. The key benefit of the mixed straddle election is that the loss deferral rule (remember, loss deferral is bad) is replaced by marking the portfolio to market daily. Call options are treated as Section 1256 positions; the underlying is a non-1256 security.

Section 1256 assets are marked-to-market daily and receive a 60/40 long-term/short-term character, while non-1256 securities have their holding period suspended, which means all gain and loss realization is short-term. Global X’s guide to calculating capital gains tax liability assuming the mixed straddle election includes several worked examples (which is solid gold in my line of work). I’ve found it very helpful.

A mark-to-market portfolio, however, has at least two tax implications:

The underlying, which may have benefited from the preposterous tax efficiency of the ETF wrapper’s in-kind redemption, can no longer take advantage of it.

Worse, the holding period of the underlying is suspended, and guarantees assignment-forced realization is always short-term.

ETFs receiving dividends generally just pass them to investors as qualified. But not always.

Dividends

Depending on the index, most dividends from U.S.-based and several foreign companies are qualified, which means they receive preferential tax treatment.

However, an observant reader may have already realized that if a fund makes the mixed straddle election, dividends are all nonqualified since the underlying holding period is suspended and, therefore, always short-term.

So many words

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve just taken a tour of the taxation of covered call ETFs. It would be really nice if there were a metric that captured all this complexity. Fortunately, Qualified Dividend Income Percent (QDI%) comes close. I’ve included some large plain-vanilla index ETFs to show how covered call ETFs stack up.

QDI% captures most of the “Quality” issues I named above but doesn’t say anything about the “Quantity” of taxable events I call the “original sin” of the covered call ETF. It also glosses over the copious nondividend return of capital these funds distribute.

But let’s leave it at that for this intro piece on covered call ETF taxation, knowing that more detail might add to the story but that the overall picture is not pretty.

Sources

Kazemi, Hossein. "Editor's Letter." The Journal of Alternative Investments 26, no. 4 (Spring 2024): 1-3.

Missakian, Vrezhui Albarian. "Final Regulations Address Gain or Loss Recognition for Identified Mixed Straddles." The Tax Adviser, October 31, 2014.

Leeds, Mark. "Do What I Say, Not What I Do: The US Internal Revenue Service Finalizes Changes to the Mixed Straddle Rules." Mayer Brown, July 22, 2014.

I thoroughly enjoyed this piece and your excellent insights on taxation. I personally use JEPQ. There’s a few points I figured I’d share. I disagree from your generalizations about lack of institutional appetite. I think you’re right, but for the wrong reason. Hamilton Reiner has introduced the first of many institutional strategies in a form/wrapper retail investors can use. These institutions have the resources needed to do these strategies manually and at scale. But the underlying strategy is used by every institution and current market regime and structure can show this. Although not tax efficient, these distribute higher tax efficient yields than most indices with similar risk profiles. For example, the quantitative metrics for a position like JEPQ offer almost all the upside as QQQ with less of the downside. It also has allowed investors to participate in a higher weighting in Mag 7 stocks versus other indices covered call strategies. Where these strategies will suffer is if there’s a shift in market structure with options premium moving rapidly. To this I’d say “Thanks 0DTE”. Overall however, statistically these strategies can produce better risk adjusted returns over multiple market regimes and cycles.