Tax Alpha Weekly

AQR: Regardless of How You Deal with Low-Basis Stock, Long-Short Strategies Can Help

Quantinno: A new conceptual framework for tax-loss harvesting with long/short extension

Invesco: Enhanced Tax-Optimized Large Cap Equity SMA (Long/Short Factsheet)

Tax Policy Center: For those with AGI over $1 million, capital gains accounted for 42% of their income

Leader

Direct indexing with tax-loss harvesting is plain vanilla. The hot “new” thing is tax-aware long-short strategies like 130/30. These strategies might produce 8x more capital losses than direct indexing for every dollar invested, according to a set of 10-year simulations run by AQR. They also offer advisers a differentiated product and, therefore, a glimmer of operating margin, which continues its multi-decade crunch. Why, then, is tax-aware long-short still so niche?

Direct Indexing Goes Mainstream

Direct indexing with tax-loss harvesting is everywhere. Startups and late entrants keep launching variations on the core themes of portfolio customization and tax efficiency. Consumer options have existed for nearly a decade. Margin continues shrinking. The word “commoditized” is used regularly.

The sameness is exhausting.

Since we’ve so thoroughly explored, both from a research and product perspective, the area in and around direct indexing with tax-loss harvesting, it’s natural, perhaps existential, to ask, “What’s next?”

One answer, unsurprisingly, is leverage[1].

A New Old Play

Tax-aware long-short strategies inject some sex into the boring world of core tax-aware portfolio management.

For decades, researchers and analysts have dumped countless hours into quantifying the value of tax-loss harvesting, culminating in a widely accepted figure of 100 basis points a year, give or take, depending on the investor, volatility, etc. [2,3,4,5]. Industry veterans tell me actual tax alpha tends to be higher in practice.

Tax alpha starts with a bang, especially in volatile years and compounds, but ultimately decays as the portfolio basis resets lower and lower following each harvested loss.

Erkko Etula, CEO of Brooklyn Investment Group, which offers a 130/30 strategy managed alongside fixed income, calls this “an ossified portfolio” in his paper on tax-aware long-short strategies.

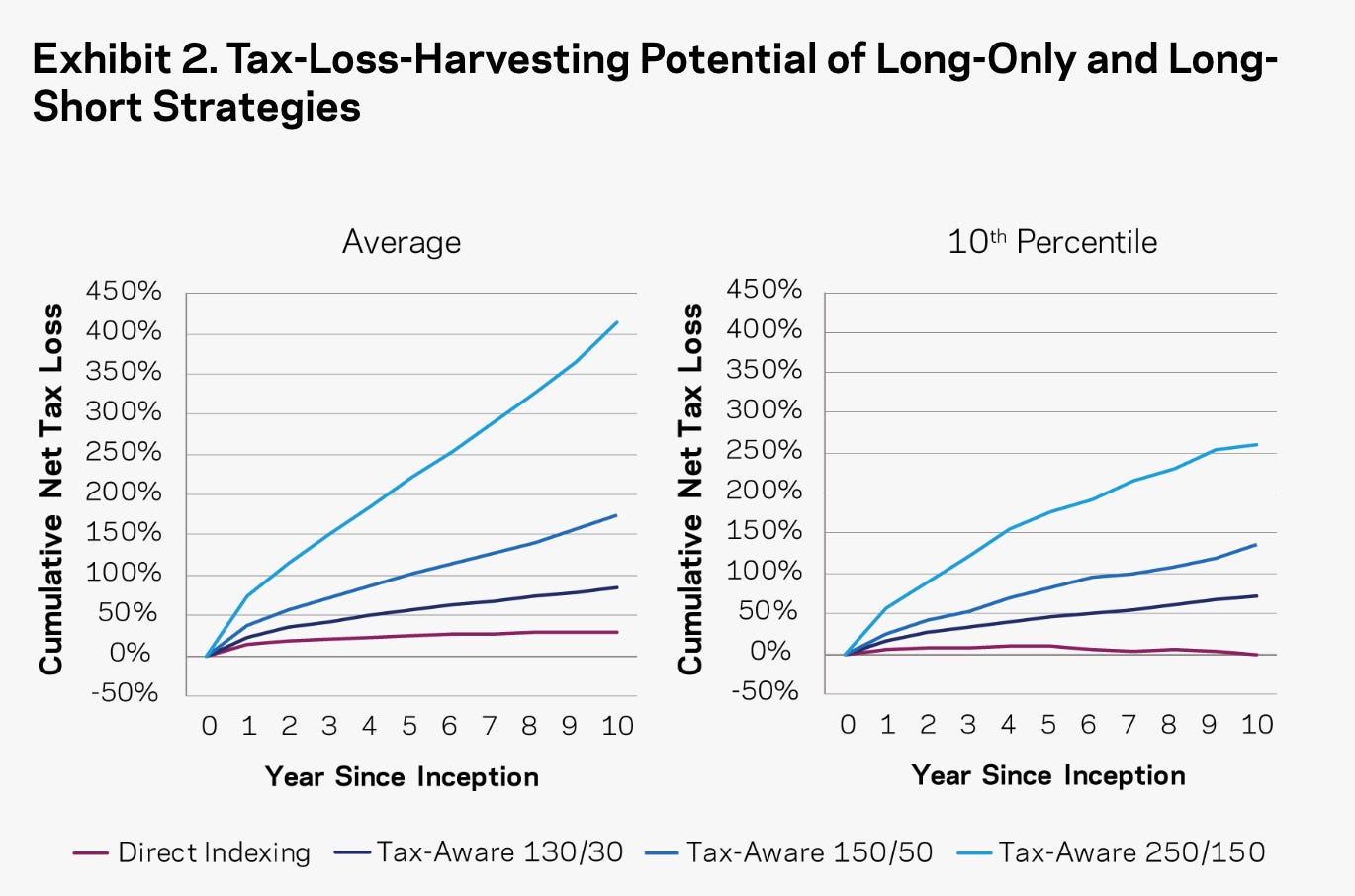

Research by AQR shows that direct indexing with tax-loss harvesting might generate $0.50 in capital losses for every dollar invested over ten years, though it is often much less. (See the charts below)

Long-only vendors argue this doesn’t matter. “There’s always motion in the portfolios… or new cash,” a few told me. “Tax-loss harvesting opportunities never fully disappear.”

However, the magnitude of harvested losses makes direct indexing an incomplete solution for diversifying concentrated single-stock positions.

Tax-aware long-short strategies are a response to the shortcomings of direct indexing.

By introducing leverage and shorting, strategies like the 130/30 – which gets its name from the 130% long and 30% short, usually beta 1.0 mandate, with some wiggle room for pre-tax alpha and conscious over and underweighting – want to solve each of direct indexing’s problems.

Managers bragging about “customization” ad nauseam can now actively short individual names.

Though some slice of a given index will underperform each year, tax-loss harvesting benefit is generally higher in down years. With short positions, there are material losses to harvest in every market.

AQR research shows that tax-aware long-short strategies with more leverage, like a 250/150 portfolio, can deliver capital losses of around $4.00 for each dollar invested (over their 10-year simulations). That’s breathtaking. And a compelling solution for unwinding a concentrated holding.

Why stop there? I’ve heard credible rumors of an 800/700 tax-aware long-short portfolio north of $10 million for a single family. Who knows what the emitted capital losses look like, but they are likely (by design) substantial.

If tax-aware long-short strategies are such deft tax-loss harvesting vehicles, and tax-loss harvesting is a big deal, why is tax-aware long-short still niche?

Why Tax-Aware Long-Short is Still Niche

I can think of at least four categories of reasons:

Macro: There is no institutional demand, and the strategy is unsuitable for most individual investors.

Risk: Even tax-sensitive advisers are wary of leverage, shorting, and the end state of a tax-aware long-short strategy.

Technical: Managing tax-aware long-short is vastly more complex than direct indexing, limiting the vendors that can deliver it.

Structural: The short rebate is not financially viable at some custodian lenders.

The audience for direct indexing and tax-aware long-short strategies is small compared to the audience for pre-tax alpha. If there is institutional demand for tax-aware long-short, it is likely privately managed (here’s an approximate example), and individuals need capital gains to put copious capital losses to use. Only about 5% of investors recognized short-term capital gains in 2020 to give a sense of those who could benefit from additional capital losses.

Pre-tax alpha is a core component of some tax-aware long-short products. The post-tax alpha is valuable, but the pre-tax and post-tax alpha together sold the strategy, as two advisers who use AQR’s solution told me.

Still, many more advisers interested in tax-efficient investing express that leverage is scary. Though a few use tax-aware long-short as a complete replacement for core direct indexing, that is rare.

A very large (you've heard of them) adviser tells me that long-short is more like an alternative strategy, even though they could make a lot of money by pushing it as a core product. Many fear short squeeze, unlimited loss potential, and unknown unknowns.

“[A] long/short book requires both active oversight and operational expertise,” Erkko Etula says, and advisers need to “incorporat[e] short availability and the cost of borrow for each candidate short position as part of the daily optimization process.”

Beyond typical wash sales and holding period and all the other details of managing a plain-vanilla direct indexing strategy, long-short portfolio managers need to keep track of collateral, margin, wash sales on the short, constructive sales, and new flavors of idiosyncratic risk.

The now classic example of short risk is Gamestop’s meteoric rise in 2021. Intraday risk management, uncommon in direct indexing, seems necessary in long-short implementations.

This comes up so often that I’ve started collecting portfolio mistake stories to understand why managing tax-aware long-short is so tricky.

In one instance, an adviser who wished to remain anonymous told me about a sub-adviser who was surprised that a short triggered a margin call, which required phoning the end customer and requesting an immediate cash infusion, or the custodian threatened to close some winning positions, thus realizing capital gains.

In another case, an adviser told me they shorted a fractional share only to be surprised that the custodian had closed the position without notice since the fraction had grown above $1,000.

“It takes experience,” Luke Smith at AlphaWorks, a tax-aware long-short hedge fund and consultancy, told me last week. Tuning portfolio constraints, he described, can have unexpected short-term consequences.

Just how much can we short? “In the S&P 500, it’s almost unlimited,” Smith said.

But even if all the risk and operational mess are buttoned down, custodians lending shares for shorting may rebate only a tiny fraction of the income generated by investing collateral posted by borrowers. The short rebate must be generous for the tax-aware long-short to make financial sense.

Fidelity is generally acceptable, Interactive Brokers is possible, and Charles Schwab is mostly not financially viable. There are likely others, but this is what the adviser community (and a glance at a handful of Form ADVs from leading providers) tells me. This will undoubtedly change as the market standardizes, but for now, short rebates are lender-specific, unlike borrowing rates, which have become more or less uniform over the past ten years.

Suppose an investor takes the plunge and adopts a tax-aware long-short portfolio for several years. Eventually, they must unwind the shorts and transition the portfolio to long-only. AQR has done some fascinating research into transitioning back to long-only (“de-risking,” discussed in great detail here). Still, the fact that a plan is necessary is just another thing for investors and their advisers to understand and manage.

Tax-aware long-short remains niche for all these reasons – perception and education, risk and complexity, technical and structural barriers, and end-state management.

Will Tax-Aware Long-Short Ever Get Big?

At least two investors have expressed concern to me that legislators will act to contain tax-aware long-short. It’s possible, but tax-aware long-short is so tiny – I estimate less than $10 BN AUM – that legislators likely have better things to do. But who knows?

These strategies strike me as early in their market development lifecycle. Vendor selection is limited, tax-aware long-short is technically demanding to deliver, and market terms, like short rebate, across a limited selection of custodian lenders, vary from viable to not. In other words, we're far from calling tax-aware long-short a commodity.

Investors meeting asset minimums with sufficient capital gains and advisers working with financially viable lenders can solve some of the gnarliest issues left behind by direct indexing. Anyone adopting tax-aware long-short could be ahead of the curve for quite some time.

This is just the beginning: I am focusing on tax-aware long-short strategies for the next several posts. Stay tuned if this intro piece did not satisfy your need for specifics. I will get into all the details in subsequent posts.

Other answers include holistic – sometimes single account – portfolio management, integration with trust and estate products, and normalization of exotic tax mitigation solutions.

Dickson, Joel M., and John B. Shoven. 1994. “A Stock Index Mutual Fund Without Net Capital Gains Realizations.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=5427.

Berkin, Andrew L., and Christopher G. Luck. 2010. “Having Your Cake and Eating It Too: The Before- and After-Tax Efficiencies of an Extended Equity Mandate.” Financial Analysts Journal 66 (4): 33–45. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v66.n4.3.

Khang, Kevin, Thomas Paradise, and Joel Dickson. 2020. “Tax Loss Harvesting: A Portfolio and Wealth Planning Perspective.”

Chaudhuri, Shomesh E., Terence C. Burnham, and Andrew W. Lo. 2020. “An Empirical Evaluation of Tax-Loss-Harvesting Alpha.” Financial Analysts Journal 76 (3): 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/0015198X.2020.1760064.

Very helpful post. Have you put together any comparisons of the various L/S SMA providers?