Are Bonds a Bigger Shitburger?

There’s a whole class of thinking that goes like this:

Bonds offer little diversification benefit under extreme duress.

Bonds are relatively illiquid versus equities (mainly a negotiated market).

Bonds distribute tax-inefficient ordinary income.

Note: Treasury bond interest is federally taxed but state/locally exempt, while municipal bond interest is typically federally exempt and often state/locally exempt for in-state bonds.

Options seem to address each issue:

Options offer concrete protection (unrelated to time-varying correlation).

Listed options are highly liquid.

Options premiums are taxed more favorably as short-term capital gains.

Note: Short-term capital gains are taxed at the same rates as ordinary income but net with capital losses, unlocking value from tax-loss harvesting.

Note: Options premiums are taxable at the federal and state/local levels.

So, when I visited CBOE last week for the RMC RIA conversations in Chicago, I was not totally surprised to hear covered-call ETF vendors describe their products as a liquid and tax-efficient complement (perhaps an alternative?) to bonds.

I previously described covered call ETFs as a Shitburger with Extra Tax. This holds up against plain-vanilla equity ETFs.

But the argument has a flip side that’s worth a closer look.

Are bonds actually a bigger shitburger than covered calls?

The Flip Side of the Shitburger

“Bonds are bad” sounds naive.

There's a giant industry dedicated to issuing, trading, allocating, researching, monitoring, and talking about them. A blanket statement like “bonds are bad” is embarrassing.

But I can't let the “bonds are bad” earworm go.

Covered call ETFs sit somewhere between stocks and bonds

The marketing is a blend of the two. Here’s language from JEPI’s 2023 prospectus:

“…seek current income…”

“…maintaining prospects for capital appreciation.”

“…lower volatility than the S&P 500 Index…”

In a vacuum, these statements seem fine.

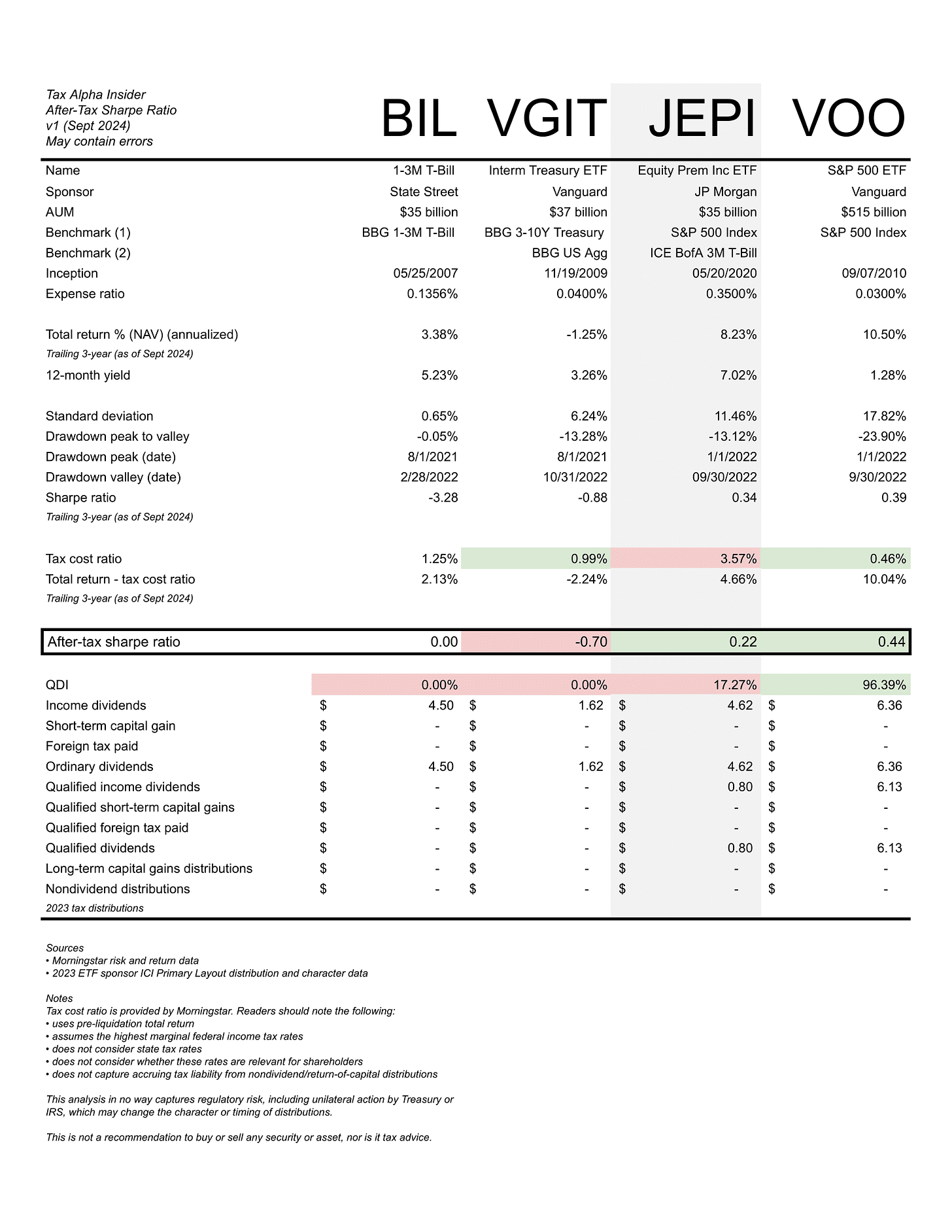

But I wanted to put these statements in context, so I created the following report comparing the JP Morgan Equity Premium Income ETF (JEPI) – the poster child for the covered call ETF ecosystem at $35.5 billion AUM (Sept 21, 2024) – to an equity index ETF (Vanguard’s VOO), and also some bond ETFs (State Street’s 1-3M T-Bills ETF BIL to represent the risk-free rate, and Vanguard’s intermediate Treasury fund VGIT).

An after-tax Sharpe ratio might help

After-tax Sharpe ratio scales risk and tax to the ETF and distills everything down to a single number that should be comparable across products. It’s not perfect (see the Notes below), but maybe a step forward.

JEPI is relatively straightforward from a tax perspective. It owns equity-linked notes, which do all of the call writing. The notes pay interest income, which the fund distributes and which are taxed as ordinary income.

The tax implications of the structural decision to use equity-linked notes becomes obvious when we look at JEPI’s 2023 QDI1 and distributions. Most of the income the fund distributes is ordinary in character.

Quick aside…

Other covered call ETFs (e.g. Goldman’s GPIX and Parametric’s PAPI) harvest capital losses that can offset premiums generated by call writing (which have the same tax character as the harvested losses), but this isn’t an option for JEPI (since the character of its income is ordinary), so the distribution story is, unfortunately for shareholders, simpler.

Things that catch my attention in this report:

JEPI generates the most income

JEPI is less volatile than VOO, but more volatile than the bond ETFs

JEPI’s max drawdown is about the same as VGIT’s max drawdown 🤨

JEPI’s Sharpe ratio is about the same as VOO, and beats the bond ETFs

JEPI’s after-tax Sharpe ratio is half of VOO’s, but still beats the bond ETFs

It’s worth noting that the data are trailing 3 years, and that’s admittedly insufficient. But my goal is to illustrate, however imperfectly, that taxation is a structural rather than a market thing, and to put JEPI in context versus investment alternatives.

JEPI produces a lot of ordinary income, which is bad, but the upside potential, however small, seems to boost it above the bond alternatives in this time period.

What Does This Mean?

JEPI, as avatar for all covered call ETFs, does what it says on the tin.

JEPI generates income with less volatility than its primary benchmark and retains some upside potential. Giving up upside potential is a hell of a price to pay, but plenty of others have already written about that.

But what about versus the bond ETFs?

“The main difference is downside risk: a bond has relatively known loss given default (LGD) over a broad diversified sample size… So if you do covered calls to generate income, how do you manage the downside?” Yang Tang, CEO of Arch Indices and sponsor of the VWI multi-asset minimal volatility income ETF, told me.

The period I examined was relatively calm. Recovering from a substantial drawdown takes a long time. Covered calls’ asymmetric risk profile means they might suffer more than bonds and take longer to recover… but maybe not.

My point is the positioning of these products deserves more thought.

It's not a covered call versus equity; it's a covered call versus equity versus bonds versus the market circumstances.

Do we need bonds?

Maybe not.

Time-varying diversification benefits are a bummer. And they're really tax-inefficient.

If JEPI is an acceptable alternative to bonds (this needs a more thorough analysis than my short time period), presumably covered call ETFs that are more thoughtful about tax could perform even better.

It’s also possible that collar and buffer ETFs could be better than that. Options allow investors to diversify more predictably without the liquidity challenges and ordinary income hassle that come with bonds.

What about credit and counterparty risk?

Opponents of options say that credit and counterparty risk in the options markets is too great to fully replace bonds.

The proponents of options say regulators want functioning equity markets, and that options need to function. In other words, options are too big to fail.

I’m still researching and making up my mind, and welcome feedback along these lines.

Where do bonds outdo the certainty options provide?

Is after-tax Sharpe ratio persuasive?

For now, I’m having trouble letting it go…

Sources

Israelov, Roni, and David Nze Ndong. "A ‘Devil’s Bargain’: When Generating Income Undermines Investment Returns." The Journal of Alternative Investments 26, no. 4 (Spring 2024): 9-26. https://doi.org/10.3905/jai.2024.1.211.

Morningstar, Inc. 2005. “Tax Cost Ratio.”

Morningstar, Inc. 2003. “After-Tax Return Methodology.”

Qualified Dividend Income (QDI) refers to the portion of a fund's net income eligible for reduced tax rates. Equity and balanced funds typically distribute QDI, while money market and fixed income funds do not. QDI-eligible amounts are reported in Box 1b of Form 1099-DIV.

![Elsa winking her eye.. 😉[by ConstableFrozen] : r/Frozen Elsa winking her eye.. 😉[by ConstableFrozen] : r/Frozen](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5efc2715-1bfc-4f00-b181-a31ebe4610fa_148x148.jpeg)

Right. Correlation feels like I'm holding my breath and hoping. Options are certain.

Wow! Thanks for providing this. I tend to believe we don't need bonds for all the points you mention. I've run these thoughts through my head and some basic analysis, nothing like what you did. After-tax sharpe is very useful. If you're using asset location and use JEPI, JEPI looks even better compared to VGIT. I just appreciate having to worry less about correlation in drawdowns.